INTERVIEW Breakbeat Lou & Peanut Butter Wolf

You can read an abridged version of this interview in Now Then magazine 24 (Manchester) and 91 (Sheffield).

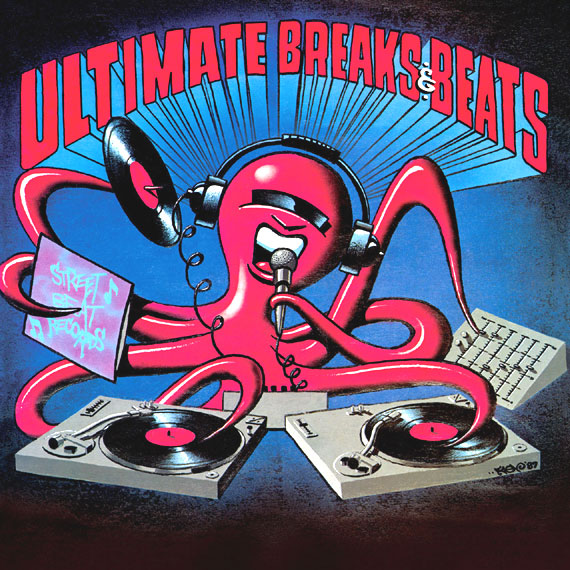

The importance of Louis Flores, aka Breakbeat Lou, to hip hop cannot be stressed enough – yet his name is not well known to many artists or fans. Last October, E (of Myron and E) had been telling me he was looking forward to watching ‘Breakbeat Lou’ play in LA the next month, and had to contextualise for me that this was the guy, together with the sadly-departed Lenny Roberts, who had put out the legendary Ultimate Breaks and Beats compilations – and that he’d started DJing out.

“Understand his name is Breakbeat Lou for a reason…”

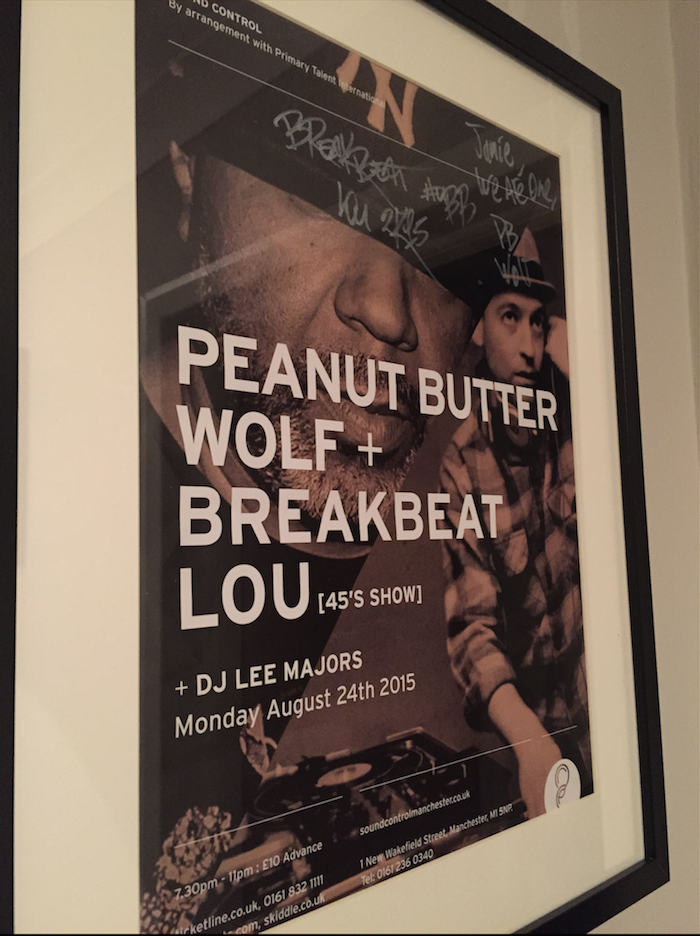

August 2015 saw him visit the UK and Europe for the first time with Peanut Butter Wolf, delighting audiences (including Dismaland’s, surely breaking the park’s rules) with 45 selections and a natural, party-rocking relationship over the decks which in Manchester took the form of hard funk, disco and hip hop fun at Sound Control. Spending a couple of days downtime in Manchester gave me the chance to sit down and spend some time in their company. “He’s the veteran, I’m the new jack here,” smiles Lou, as Wolf settles down with their retrieved laundry and we wait for a couple of 2-for-1 strawberry cocktails to arrive. The Turtle Bay restaurant on Oldham Street has a Manchester icon adorning its side wall outside, Timperly’s Frank Sidebottom. If you’ve seen My Vinyl Weighs A Ton, the Stones Throw label documentary, you might understand why he reminds me of Wolf’s Folerio alter ego a little. It’s because of Wolf that Lou’s over here, at the gig the night previous the crowd giving Lou a big hand for his “first time out of The Bronx”, as Wolf put it.

“Well, first time outside of the United States – I’ve done LA, I’ve done San Fran, Oakland, Minneapolis, Las Vegas…”

“But even those have been recent,” Wolf points out.

“No, Minneapolis was two years ago.”

“That’s recent!” The two laugh, a nice indication of their nurturing friendship and mutual respect. This tour is about Lou really, Wolf providing an affirmation for Stones Throw fans and others that this is a name you should know about. Because while the UBB series ran from 1986 to 1991 on Street Beat Records, Lou has kept his head down and away from the industry since the mid-nineties. It was Breakbeat Lenny who was better known as steerer of UBB, with some assuming that ‘Louis Flores’, credited as editing some of the songs, didn’t actually exist. Read a great article on all that here.

“Well, I just got back into the game 2010. I had left in ‘95, totally, then came back 2009, and hardcore 2010. I’ve just started the travelling more or less the last couple of years.” Has he noticed much difference in audience responses in Europe as opposed to home? “Oh, most definitely. A little more accepting, a little more versatile in the ear, in the palette of music they decide to receive from us, and I think they appreciate what we bring to them. It’s not just they have a certain amount of expectation of what they’re gonna get from us, things they most definitely want to hear out of us, but they’ve been accepting whatever we’ve able to present to them, for sure.

Last time I caught Wolf playing was in 2009, when Manchester’s Disco 3000 brought him, Dam Funk, James Pants and Mayer Hawthorne to The Deaf Institute just after Mayer’s heart-shaped Just Ain’t Gonna Work Out was released. “It’s really a case by case. Some cities are better than others, then even within the cities, like sometimes it’s a different promoter that knows how to get the right audience. I’ve played great shows in London and decent shows, it just really depends on who’s doing it.”

In a couple of days, the duo are due to play Dismaland, a good look on Lou’s first trip to Europe. “I think it’s outstanding! We’ve been more than blessed on this trip for sure. Besides the audiences, there’s been a lot of positive things that have come out of the locations we’ve been at. Dismaland’s gonna be the pinnacle of exposure for us.” Noticing Lou’s large grin, I remind him that he’s not going to be allowed to beam like that over there. “I don’t smile anyway,” he chuckles. You look at my pictures, you very rarely get a smile. You don’t get no smile, you don’t get no eyes. No eyes, brim low, no smile.” The media have been all over Dismaland in the week preceding this gig, and it’s great to see Run The Jewels, DJ Yoda, Wolf and Lou get mentioned even though most of the newspapers probably don’t even know who they are and haven’t entered into any commentary about why specific acts were chosen to perform.

Wolf reveals it was (Stones Throw heavy hip hop makers) Quakers, Portishead and Drokk (a 2000AD inspired soundtrack) producer Geoff Barrow who put them on it. “Well, Geoff Barrow I’ve known for years, we were coming over here to do, really at first only two festival dates, then we kind of built stuff around it. When he heard we were here, he was like, ‘Oh, we got to get you on this’. It was top secret until this week, we knew all along but we couldn’t say anything.”

I had promised Wolf the night before that this wouldn’t be an inane interview (“Yeah, don’t ask me where I got my name,” he’d forewarned) but the basics must be known: where did they meet?

When I explain to people and say Breakbeat Lou, they don’t know who that is, then I say the guy who did Ultimate Breaks and Beats… but to a lot of people we have to explain what that is.

Lou explains: “I got connected with him indirectly through the Beat Junkies and J Rocc. I can probably say this very freely, he’s a fan as a well as a contributor. We developed a social media connection and the biggest thing was, he had his birthday party in New York, and he just invited me to meet there. ‘Come through,’ that was the first email. Second email: ‘Come through… bring some records.’” They erupt with laughter – Wolf asked Lou to come and work?

“It’s my birthday!”

“He goes, ‘It’s a private party, no big thing, just you, me and Prince Paul’. How can I say no to that? That was in a nice little out of the way place in Brooklyn, we rocked out, it was dope, then he released the premiere of his film (the aforementioned My Vinyl Weighs A Ton), in New York. He calls me back, he says, ‘Yo, come through. See the film, bring some records’.

That must have been exciting for Wolf. “Yeah yeah, absolutely. I saw him on, I don’t know if it was Twitter or Instagram, but I noticed that J Rocc was commenting on stuff, and I was like, ‘Oh shit, that’s Lou from Ultimate Breaks and Beats?’. J Rocc put me in touch with him originally.

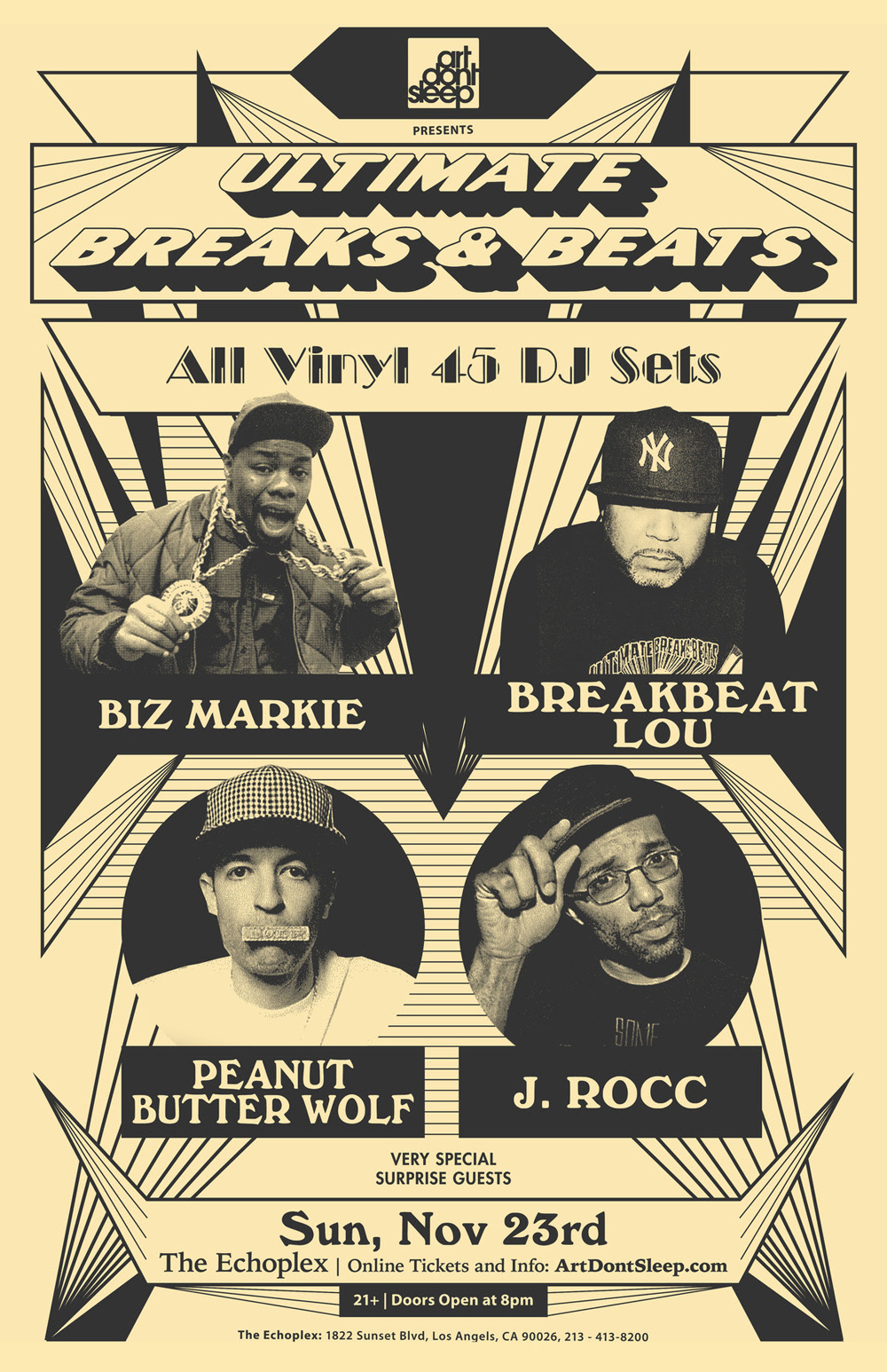

“And then what happened, the catapult of this was I got to LA to do a gig for the Beat Junkies and it got cancelled, so I ended up doing the (Beat Junkies’ weekend party) The Do Over. (Wolf) found out I was in LA, and was like, ‘Oh man, if I’d have known… next time you come to LA, let me know and I’ll rock out with you no matter where it is, we’ll make it happen’. So I said I was thinking of going back in November, so he goes I’ll talk to J Rocc… long story short, out of this simple conversation he made this phenomenal event that was three cities in California that we ended putting a spark in, certain vibes as far as DJs rocking together, he co-ordinated and it ended up being a big event between J Rocc, Wolf, Biz Markie and myself along with Supreme La Rock and Rhettmatic.”

Wolf nods, “There was over a thousand people.”

“We packed out the venue and we had everybody from Mayer Hawthorne to Madlib…”

“A lot of people jumping on stage, Pharcyde, (eighties soul singer) Howard Johnson…”

“Percee P… it was incredible. It was a DJ event, on a Sunday, and you had this kind of thing. It was incredible. He approached me and said he was willing to rock out wherever. That took place, then two other events, and we ended up on an almost two-week tour.”

Since Lou has come out of hiatus, are people getting used to the idea of him being out there? “I didn’t even know him as Breakbeat Lou, just Louis Flores (as Lou was credited on the UBB sleeve),” Wolf glances at Lou. “When I saw that as your tag on social networks, that confused me. When I explain to people and say Breakbeat Lou, they don’t know who that is, then I say the guy who did Ultimate Breaks and Beats… but to a lot of people we have to explain what that is. We met Ice Cube last week (in London, for the Straight Outta Compton film premiere), and explained what Ultimate Breaks and Beats is. He didn’t make the music on those albums, it was Dr Dre. You listen to NWA’s (first) album and eight out of twelve tracks are Ultimate Breaks and Beats. That whole era is pretty much like that.”

Lou agrees. “I think, most definitely being involved with Wolf, has made it possible to a different amount of exposure to names that are synonymous (with the scene). It’s true, like he says, people don’t correlate Ultimate Breaks and Beats with Breakbeat Lou, or correlate Ultimate Breaks and Beats with hip hop in general, because they don’t know what’s behind the scenes. Only the producers, some of the artists may know, but the younger kids, at least in their twenties now, have no idea what I contributed to the culture. The exposure that he’s enabled me to have has let me gain a new audience as far as my contribution to the culture that everybody’s in love with.”

There’s no ego whatsoever. We get the mutual respect and respect the lanes that we carry and compliment each other every which way.

There’s an assumption that rappers and producers know everything about their scene. But they’re just people. It must be like going up to William Shatner and asking him specific episode details.

“Exactly,” says Lou. So how does he find travelling with those rare 45s? That must be a little nerve-wracking. “Well, with me they go everywhere. They don’t leave my sight. On the plane, that’s my carry-on, I’d quicker lose a tonne of luggage as far as clothing or anything else, than lose those, because those are almost irreplaceable. I’m just glad it is 45s, not twelve inches, because besides the cost, your back could be broken. Right now it’s convenient, and thank God that I’ve been able to have certain pieces that only a few are able to obtain and that’s made it interesting for us to present to an audience and say, this is how we come off.”

I had noticed at the gig that while Lou sported a swish 45s record bag (I think the Rich Medina x Tucker & Bloom one) Wolf had a bright orange plastic toolbox. Was it just a toolbox? “Yeah, mine was a toolbox. It’s just really lightweight and pretty durable. I got one at this place, Home Depot, in the US, it’s kind of a chain warehouse store. I just bought a second one for this trip. It’s like 20 bucks.”

Lou is busy chortling. “It’s the best thing in the world, ha ha. That’s awesome. That’s the way that he is. I’m the same way, there’s some originality to him and a certain amount of, um… courage, to say, that’s why we get along so well. He’s predictable, but unpredictable. That makes it interesting… The best thing about coming alongside him and rocking is that he has his edge in this game and his history, but there’s no ego to it. There’s no ego whatsoever. We get the mutual respect and respect the lanes that we carry and compliment each other every which way. There’s never a sense of, ‘this is who I am, respect this’.

When the two started to become friends, Lou was already well aware of Stones Throw’s output. “Oh, most definitely. When I came back into this game, I’m a student wholeheartedly, so I’ve always done my homework. Coming back, even listening to certain things, I didn’t know afterwards that it was his label, but when I came back in 2009, 2010, then the common denominator was Stones Throw and I said, ‘wow’. So when I got to meet him, it was an honour. Then I got a plethora of information about things he’s been involved with, and how much of a staple and footprint he has in this game – people have no idea. Even though the film that he put out is getting more depth into him as a person, that correlates with him as a professional, that correlates with him as a fan, that correlates with him as an executive, just brings a pleasant taste to see that somebody can be across that whole spectrum and not get caught up with their success, their ego, their place in history. That’s a beautiful thing to be a part of.”

Earlier in the day, the two had been digging in the crates of Beatin’ Rhythm, a world famous 45s spot. Is it still exciting to have that opportunity, or do they feel like they’ve seen it all? “I do (dig) on tour when I’m able to,” answers Wolf. “I chose Manchester to have the days off because of Beatin’ Rhythm, I always find something there. A lot of records that people know about have been picked through but I my taste isn’t necessarily what everybody else wants anyway.”

“With me it’s a different story because I’m a recovering addict,” Lou laughs. “I purposely, when I go anywhere, don’t make any room so that I can’t buy anything. If not, it gets crazy. I found four records today… well I saw four records, I think I gave him three. There’s so much stuff that I can see. I’ve been blessed to have more or less everything I wanted. If I had room, I would’ve been buying doubles and triples of a whole bunch of stuff.” He could always buy a toolbox from B&Q. “Ha ha, na. It’s just too bad. It’s very bad.”

What about a holy grail record? Is there anything they’re after that they haven’t been able to find? “Like I say, I’ve been blessed to have a lot of stuff. I’m pretty sure there’s a lot of stuff I don’t know about, because records are endless to me. In every market in every country, they have their underground cream of the crop records, but as far as off the top of my head, na I think I’m good. I’m pretty sure if I go hardcore and start digging, I’ll find tonnes of stuff. Times change, your palette of what you’re looking for tends to change. There’s a lot of stuff that people are looking for, for samples or boom bap drums, that’s simple. I’m looking for… I love structures of records, the full soul of a song that you can really feel what the artist was bringing across, and there’s different grooves that you feel at different times of your life. Right now you can get into an enormous amount of music and never be completely satisfied. There’s too much music out there.”

Wolf is blunter: “Yeah, not anything I would mention in an interview.” He laughs again. “I’d just be shooting myself in the foot. Yeah, there’s a few… like he said, most of it is stuff I don’t know about. I’m more interested in discovering stuff. That’s why I went there today, more than going to find a certain record. I go and I basically will spend hours and hours and just listen to everything.”

Lou’s hiatus took place to get away from the darker side of the record industry and for him to be able to spend more time with family. Has getting records out of storage been a slow process? “It’s been a very slow process. At the beginning it was more of a show and tell kind of thing, I didn’t get into the DJ mode until, I would say, late 2010. When the whole process came about of people going, ‘We need you in this game, we need you back’. Records were a way, like a show and tell kind of thing. People would say, ‘Oh I’ve never seen that on 45’, or ‘I’ve never seen that twelve inch or promo’. The whole infamous #45Fridays started like that, it was a conversation between myself, Kenny Dope, DJ Spinna, DJ Scratch – this was right after our Biz Markie performance – then you got J Rocc and Rich Medina chimed in afterwards, and people from other parts of the country. The four of us had dinner, and Scratch said, ‘Tomorrow we’re gonna put up all-UBB #45Fridays’ (on Twitter), and that’s how it came about. I was in awe. They said Louis, bring some records out. So I brought a couple of things out, and then a couple of things became… well, I spent enormous amounts of money getting records out of storage.”

Is there a sense of being reborn over the past five years for Lou? “l left the industry, I didn’t leave music. It was two different things. When the digital age came about, I was having people already transfer stuff from my collection into MP3 form so the music was always in my ear. I never stopped listening to say, my James Brown records, or my Dyke and the Blazers, those records were always being listened to some how, some way. Even all the hip hop stuff I have that I like, it was all being converted. The change as far as the excitement came was really seeing what impact UBB had in the industry. I left in ‘95 and had no idea what kind of impact… guys like Wolf were telling me who had used this, then finding out in the long run how much of an influence it was not just in hip hop, in music in general. From everybody from Mariah Carey, Janet Jackson to even Hanson, that sampled elements from UBB. Then even more so, how much impact it had on hip hop afterwards, from the J Dillas to the Pete Rocks to the Premiers, to Just Blaze, these guys that were shaping the ‘90s and 2000s era of music were influenced by those records, and I was really taken aback by that.

“Then you have label executives like Wolf that were also influenced by it somehow, some way, so it just brought back a charge to the love for the industry. Not a love for the music, but for the industry that was still intact from the original exception of the essence of it. It was beautiful.”

Lou licensed tracks for the UBB com using mechanical licensing (which granted him limited permissions to re-edit some tracks) – have either of them come across any barriers with regards to their labels or releases?

“No, I never had that issue, because again I did everything through Harry Fox, who is a broker who took care of all our releases, so we paid him and that was that. The only barriers that I’ve had before, or gripes, were people who did not have the proper information, saying they were bootlegs and they weren’t.” Before the legit UBB series, Lenny and Lou had put out eight volumes of Octopus Breaks. “The bootlegs stuff was the Octopus, I have no problem saying that, we did that. But everything that was on UBB was through the proper channels. If people was to do their homework, they would know that the records were being pressed up at Specialty. Specialty Records was owned by WEA distribution which is part of Warner Brothers, they didn’t press up no bootlegs. Our records were being mastered at the top mastering company in New York, they didn’t master bootlegs. Our collection was co-ordinated by this company called Music Connection, which was a big broker in New York, they didn’t deal with bootlegs. Our cover was being printed by Ross Ellis, a big company that did all the jackets for records, they didn’t deal with bootlegs, so if you knew all those things were intact, then how would people still speak sideways and say, ‘these records weren’t done this way’? The reason why the credits were put on the back, that’s because that was one of the requirements that we had to do because when you follow the mechanical licensing for compilations, that’s what you have to do. You don’t have to name the artist, but you have to name the writers and publisher. That’s why that came about.”

It’s a milestone – thirty years of a piece of any kind of creation to still have some kind of relevancy I think is pretty cool. That’s the pathway for next year for sure.

Thinking about barriers, have major labels ever sniffed around Stones Throw? “I’ve had offers from major labels but it was never anything I was interested in. I do Stones Throw because I like the creative control. It’s worked for 19 years the way it’s been, and I wouldn’t necessarily want to do it differently at this point. There are artists like Mayer Hawthorne, he’s done stuff with major labels, but he still works for Stones Throw as well. Aloe Blacc was a situation where it was just, the music wasn’t.. the direction he was going was not really the direction that I was in with Stones Throw so it wouldn’t make sense to continue working together that way.”

Both Lou and Wolf lost people close to them directly linked to their musical output. Breakbeat Lenny passed away in the early nineties, and 2016 will see the tenth anniversary of Dilla’s passing. Is there a feeling that there are appropriate ways to pay tribute to their friends? Every year at Dilla tributes there are certain voices that murmur, ‘it’s too much now’.

“My thing is, the best thing is to respect the legacy itself. As far as doing tribute nights, that’s cool if it works, but one of the reasons I came back is loving the music, the constant of hearing the bootleg records and how much we bust our butts to get this thing done, it leaves a salty sourness. That’s why I made a point to tell people the truth behind it. Lenny was a quiet person to begin with, so the hoopla and thing he wouldn’t like that. It was about his music and his business and that’s it. Lenny, when he was alive and we used to go to places, Lenny very rarely went somewhere to hang out, that wasn’t his thing. He hung out at Bronx River (Bronx River Houses, a housing project in the Bronx where hip hop was born, and many DJs got their start) because there was other personal reasons that he hung out there but he wasn’t that kind of person. He was subdued in the corner, chilling, listening to his music, smoke his cigarette, drink his coke and call it a day. That’s the way he was. The best way I could honour him was to maintain the profile that he always had, as far as my situation is. As far as UBB, when I came back I started a tour that didn’t go through, but I feel comfortable that next year it is the thirtieth anniversary and I should do something for it. That’s why a lot of stuff is being put into place to make that celebration. It’s a milestone – thirty years of a piece of any kind of creation to still have some kind of relevancy I think is pretty cool. That’s the pathway for next year for sure.”

A guide to the Breakbeat Lenny archive at Cornell University, NY

Wolf’s initial tribute to Dilla wasn’t planned that way. “When he was alive, and he recorded Donuts for us, we had record release parties worked out. And then he got too sick to play on them, so J Rocc and I came with an idea, why don’t we play all Dilla songs at it. We thought he was gonna be there in the audience with us and we invited him out and he was in the hospital.” He pauses. “No he wasn’t, this was before Donuts… so Donuts was supposed to come out in November, but it got pushed back to February because there were too many records coming out in the fourth quarter and our distributor told us to push it back. So we said we’ll put it out on his birthday. That’s what we did, and he died three days later. The early (parties) were with J Rocc and I. Actually at his wake, we decided we would go through our hard dives and find all the Dilla songs we had and we came up with, I think, ten hours worth of music or something like that.

“After he passed away, to me, it got a little out of hand with all the Dilla tributes but if Ma Dukes asked me to do a Dilla tribute, then I’d do it. If it’s anything to help his surviving family members, his kids and his mom, that makes a lot of sense. I’m not totally against doing tribute nights… I just didn’t really want to be known as the DJ that’s trying to make his name off of somebody else. When Dilla was alive, we were pretty good friends. At the funeral, his mom asked me to choose the flowers for the casket, I was kind of more involved in the behind the scenes stuff than being like, ‘I’m Peanut Butter Wolf, and I’m Dilla’s friend’. It’s hard to explain. I guess the short version of it is that since he’s passed I’ve played very few of the Dilla tributes, but I’ve gone to them and it’s fun to hear his music, it’s exciting and it ages well even though the music is many years old, and we’ve heard it over and over again, but his legacy is not going away any time soon.”

Dilla’s name was mentioned the previous night at the gig, when the crowd went wild to a little Dilla. “We bring records,” Lou expands. “Some of the records happen to be Dilla samples. Somebody shouted, ‘Play more Dilla!’ when he played Dionne Warwick…

Wolf clarifies, “I love playing Dilla. But I don’t normally do a whole set of Dilla. I’ll do a Michael Jackson set on his birthday,” he laughs. “But I don’t wanna be known as the Michael Jackson DJ either.”

“With it being a hip hop crowd and them knowing the label (Wolf) was from, they’re going to expect him to go ballistic on Dilla stuff,” Lou says. “Like I say, he’s very unpredictable. There’s more than one style of music out there we can play.”

Stones Throw were one of the first labels to sign up to the music subscription service Drip, which drops all new releases (and some older ones, like Donuts) in a user’s crate for $10 per month. It’s a method that’s worked for me personally, as it still feels cheap enough to justify going out and buying the occasional vinyl release that I’ll already have digitally. Does it feel like an effective way to tackle the way people consume digital music? “I haven’t really followed it that closely – it was something that the Drip people approached (ST art and web director) Jeff Jank about and he was really excited by it. He took charge of that stuff and there’s definitely a turnover of people, some people leave and there are some new people, but it’s something that’s worth doing still.”

So, the thirtieth anniversay of UBB beckons next year. Are there plans afoot? Lou shoots Wolf a look and another grin and starts laughing. “I’ll say this much: next year will be an extremely visible year for UBB. That’s the best way to describe it in many ways. There’s gonna be everything across the board from merchandising to everything else.” He’s said too much already, and laughs again at a silent Wolf. “That’s the best way to put it right now.”

Did he ever get any flack for ‘exposing’ the samples, or conversely ‘providing’ them to be sampled easily? This ruffles his feathers a little. “It’s happened, then I’ve shut it down. This is what I say: when we came out with what we came out with, hip hop was in a real dangerous transitional slope, right? The DJ was being phased out of the equation, per se, plus whatever the DJ was doing at the time to rock with emcees in those days, they were rocking more other rap records (than original breaks). So the essence of the boom bap funk , the grimy aspect that was the original part was being lost. Why? Two-fold: the kids didn’t know the records, and if they knew the records they didn’t know where to find them. The digging spect wasn’t what it was. So, we decided to follow the Super Disco Brake’s (sic) trend, because they were doing this shit, the breaks aspect, but they were called ‘disco breaks’. We came up with the thing, if we want to preserve the DJ culture, what better way than to facilitate the element that made it what it was, the original records. So that’s why: one, to give these kids the records to utilise. Two, from an economic aspect. You used to buy Cheryl Lynn, the Incredible Bongo Band album and Herman Kelly album would cost at least $16-20 (at that time you were paying $6.39 for an particular album), then you’re buying doubles… the scale of it was very different then. It was more user friendly, because 90% of the kids could not DJ, or was as technical as Flash or Theodore, so that’s where the editing came into play. It was more of a tool for that new generation of DJs, so that the culture continued to have a flavour of its inception, than just some records put out to make some monetary gain. I speak for me, but I’m sure Lenny felt the same way, it was giving them a tool so that crowd can be continued instead of just having what I call the drum machine era of hip hop, because any record that came out at that time, there was no record that had a sample that hadn’t been figured out at that time. That’s why we came up with it.

…you gotta understand something. Our collection was like a subculture. Only hardcore DJs and hardcore diggers and producers gravitated to them, even though, if you look at our albums, we could’ve easily used beats just by themselves, but we felt that some of the songs needed to be exposed because they were big songs for us!

“One through nine and Octopus were all foundation breaks. Anything you heard at Bronx River, that’s what those beats were. When we came out with UBB, that involved the foundation breaks plus the first layer of digging. Which was the Johnny the Fox (Thin Lizzy), the Funky Drummers (James Brown), the Ashley’s Road Clip (by The Soul Searchers), those kind of records. Then we took it to a next level, which was the hardcore digging, that’s when you got the Stanley Turrentines (Sister Sancitified on UBB Vol 14), you got the Freddie Scotts (You Got What I Need, Vol 24), you got the… who was the other people that did something crazy you didn’t know… you got the L.L. (Bonus) Beats (Vol 17), people didn’t know what the heck those beats were (it was the break from Fancy’s Feel Good on loop). We wanted to spark something in the new generation to not get stuck in this little area of records, that there’s a whole plethora of music that you can search for and look for. So that’s why – those two layers of things that we decided to incorporate when we did UBB especially.

Listening intently, Wolf asks, “Did it go bigger than you thought it would?”

“Oh, without a doubt. I had no idea. I had no idea that it took… I knew sales were good, but I didn’t know of the impact it had on the industry.”

Wolf: “But it was more for DJs and collectors at first, and then when sampling came out…”

“When sampling came out… when Marley Marl decided to sample (The Honey Drippers’ Impeach The President) as the foundation of a record (MC Shan’s The Bridge in 1985), then that’s when the floodgates opened.”

Many people have pointed Lou to instances where his edits of records, lifted straight from the UBB vinyl, have been used in well known songs. Knowing that people have used his edits, is there anything Lou would have done differently? And how does he keep so calm about that? He laughs at the questions, and must have gone over this a million times in the past few years. “That’s a loaded question! Everything happens for a reason. For people to utilise something and then not give the proper credit, it is what it is. If I know the trueness of the culture and know about it, like if you and Wolf know that that was created by me, then I’m good. I’m good. I’ve come to peace with that, most definitely I’m good. But sometimes, it kills me to hear (Eric B and Rakim’s) ‘It Takes Two’? Yeah, it kills me sometimes, but to the point that that I don’t even bring the 45 with me!” Wolf chuckles at this knowingly.

“People know. It’s gotten better,” Lou continues. “When they hear that, ‘Oh yeah’, everybody thinks that’s Rob Bass but the inception comes from us. Trust me, when I came back it really hit me hard. Then in the last couple of years it’s gotten better. I’m being human but I was like ‘What?!’. My Philosophy (Boogie Down Productions) hit me hard. It Takes Two hit me hard. Raekwon used the Roy Ayers, hit me hard. And then, I didn’t even know, when I heard Straight Outta Compton I was like, ‘What the heck?!’. (Wolf) pointed that out to me, it took an acute ear to listen to that whole bottom beat. And F The Police – ‘you gotta be kidding me’. I didn’t even pay attention to it that closely until recently. Questlove, he was the one that started it, he was like, ‘if you listen to Impeach The President, the sample, you can hear this little click that sounds like a high hat, but it’s not a high hat it’s a click that’s the part of the record that was probably picked up in the groove when you recorded it and you never heard it’. I’m like ‘wow, you gotta be kidding me’. But in that sense my heart of hearts is satisfied because that was the essence of why I was really in it, for DJs, but we had no idea that it was gonna take it to the next level. It still served its purpose, I guess.”

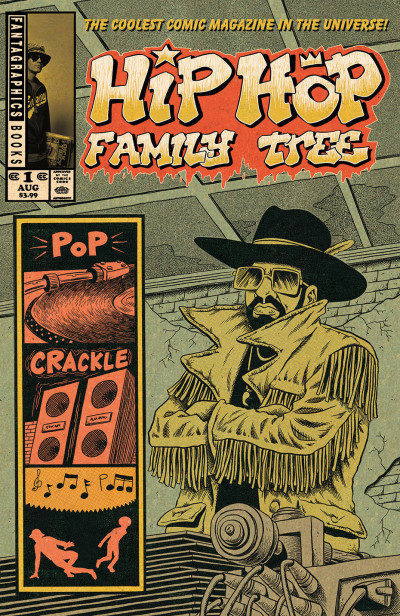

I’ve brought along a copy of the first monthly issue of Ed Piskor’s Hip Hop Family Tree comic book, out the week previously. It’s been on the table and both Wolf and Lou have had a quick flick through it. It’s many people’s entry into the history of hip hop, the three oversized volumes so far selling brilliantly through mainstream book shops as well as comic book shops. Between this, DMC’s graphic novel launch and Marvel’s tributes to hip hop covers, the two seem to be coming together much more often. I ask Wolf if that seems a natural relationship? “Yeah, it makes perfect sense. I never collected comic books. I was big on baseball cards, but I love this one, I’ve been reading it.”

It’s not just comic books that hip hop heads go nuts about. “There’s a lot of unknown factors to our culture which were embedded from the beginning. Skateboarding was there from the beginning, comic books was there from the beginning, kung-fu flicks was there from the beginning, certain games that we played. We know the five elements which is the most visible, the writing, the emceeing, the DJing, the b-boying then the knowledge aspect of it that we do on a regular basis, but it’s a little more intricate. Like skateboarding, I was skateboarding back in ‘73 myself, so we all had those friends. Professional wrestling was a big aspect of hip hop, listen to any guys coming up in the eighties or nineties, they know every freaking wrestler that was out there. I was the same. I was into comic books, baseball cards – I was talking to (Wolf) about those, I was carrying them since the late sixties. All them (kids) in hoods in the United States were gravitating to them. Comic books, I still have my Fantastic Four origin, when certain comics would come out I’d pick them up, when Superman got killed by Doomsday, I bought that, when the Batman film came out and they released those things, I bought those. My son picked up that trade so that he wants to write a comic book himself. I’m sure (Wolf) has similar stories himself, we were talking about baseball cards the other day, and he still has all that stuff. Playing marbles, playing Topps, in those days it was all over the neighbourhood when we were growing up.

Lou picks up the comic. “To me, when I get to read it it’s gonna be bugged out because I may have a different recollection…” I presume he must be in it at some point. “You’d be surprised, you’d be surprised. Again, you gotta understand something. Our collection was like a subculture. Only hardcore DJs and hardcore diggers and producers gravitated to them, even though, if you look at our albums, we could’ve easily used beats just by themselves, but we felt that some of the songs needed to be exposed because they were big songs for us! They were records we would hear in our homes, our house parties. The same way, I’m pretty sure a person that’s not into hip hop at all in 1986 woulda saw the compilation album of Volume 3, which had (Incredible Bongo Band’s) Apache, (Herman Kelly’s) Dance To The Drummer’s Beat and Cheryl Lynn’s) Got To Be Real and say, ‘Hey, I know (these songs)’, at $6.39 they didn’t have them on 12” or LP, well Apache maybe, ‘let me buy this, I don’t have these two records.’ Customers that I know have said, ‘Hey, I’ve seen that shirt somewhere, I have an album at home’, that I know don’t have nothing to do with hip hop. Because those compilations had a generation of great music throughout, all the way up from the sixties to the eighties. We had from Billy Squire, to Jack and Diane, which all came out in the eighties, that were part of these compilations. A person that mighta liked Jack and Diane, because it was being played on Kiss FM in New York, may not like the rest of his album, but might like Dyke and The Blazers because they heard Jack and Diane on Kiss FM. We were able to pile a certain sprinkling of regular audiences buying those records, not just the regular hip hop fans. Like when you say hip hop was born in ‘73 – the name ‘hip hop’ didn’t come into play until at least ‘82, so… to say it was born in ‘73 is a little bit of contradicting kinda thing, y’know? Semantics, to a certain extend I guess, but I’ll leave it at that,” he says, trailing off into laughter.

Mild High Club, on Circle Star Records

Talking about audiences reminds me of the Stones Throw crowd. Wolf recently launched another sub-label, Circle Star, which he’s moved Vex Ruffin across to. Has he felt pressure from the fans to deliver more hip hop, for instance? “There’s a lot, yeah, there is a lot of pressure from the Stones Throw fanbase, not from everybody but I was reading a lot of the YouTube comments. More importantly than that, artists that weren’t fitting the Stones Throw mould just weren’t getting fans. Vex is a perfect example.”

The Drip subscription is good for that though, as people may check out stuff dropping into their email that they may otherwise not have. “I think Stones Throw’s biggest records are hip hop records. Kinda like, more avant garde hip hop like Quasimodo or Madvillain, but still hip hop nonetheless. Donuts. When Donuts came out people were complaining that the songs were too short. It got bad reviews. Then he passed away, and it got good reviews.”

“That’s what I respect about (Wolf) the most. I respect his integrity he does as an individual and as a label, it is to be admired.” Lou is speaking from experience here. “You have to maintain some kind of structure in what you do. If you can’t maintain that structure then you can forget about it. He does his homework, he does his due diligence to make it evident when you see releases strategically put into place to make sure it’s given the best chance possible. That’s the way hip hop has always been. You take steps and you take chances, you do what you have to do, and you maintain the course that you feel is best for what you do. I think that’s probably one of the best things I know, I have no problems co-labelling with him because he has that disposition, it rocks.” Hopefully that’s a pointer to Stones Throw x UBB business to come – whatever may be due, it was a pleasure to have Breakbeat Lou over on these shores for the first time to share his selections.

Ultimate Breaks and Beats Facebook

Breakbeat Lou Twitter