Groovement Interview: Waajeed

When I arrived (in Manchester), you know I haven’t been here in years, I can’t remember the last time I was here… this place felt deeply familiar when I touched down. It feels extremely familiar, familiar in a way that’s kinda spooky. I think that I recognise this resilience that comes from the city. As a regular digger (I use the term loosely as Jon K or Darren Laws usually handed me new shit on entry, thus saving me finger blisters) down at the legendary Fat City Records in Manchester, it was inevitable that I would cross paths with Waajeed’s music. His work as the frontman of Platinum Pied Pipers for the Triple P album on Ubiquity was a firm favourite in the shop, but it was the two 12″ EPs that made up The War LP in 2007 that really cemented his work in my ether. Blatantly influenced by sounds far and wide, seeing him play at club night Friends and Family (with Ta’Raach on the mic) upon its release was a memorable experience.

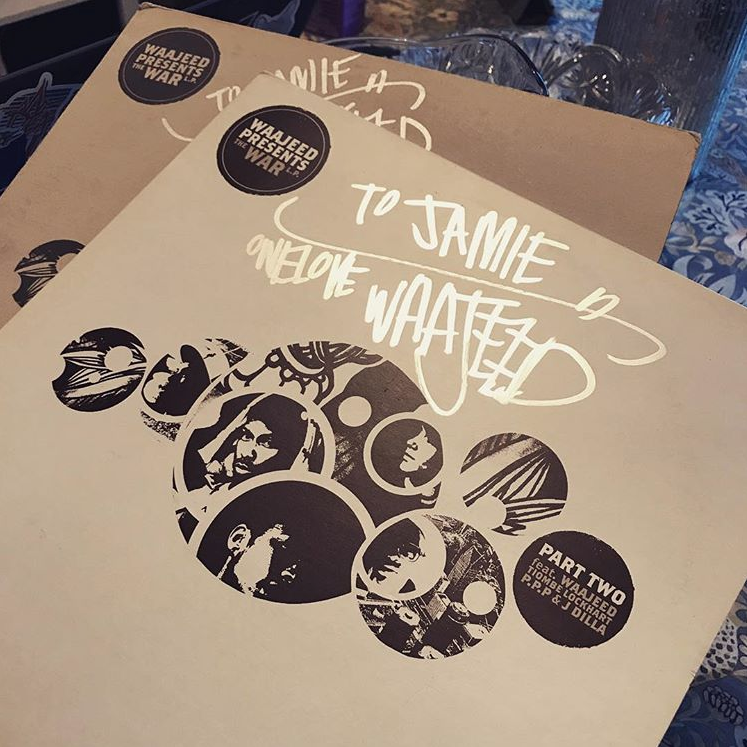

As a regular digger (I use the term loosely as Jon K or Darren Laws usually handed me new shit on entry, thus saving me finger blisters) down at the legendary Fat City Records in Manchester, it was inevitable that I would cross paths with Waajeed’s music. His work as the frontman of Platinum Pied Pipers for the Triple P album on Ubiquity was a firm favourite in the shop, but it was the two 12″ EPs that made up The War LP in 2007 that really cemented his work in my ether. Blatantly influenced by sounds far and wide, seeing him play at club night Friends and Family (with Ta’Raach on the mic) upon its release was a memorable experience.

Waajeed cut his teeth with Slum Village back in his late teens. He helped form the crew in 1991 with T3, Baatin and Jay Dee, and soon found himself on tour in Europe. He was the first to put out instrumental work from Jay Dee on his own label Bling47, something which Dilla was skeptical about there being a market for.

There was.

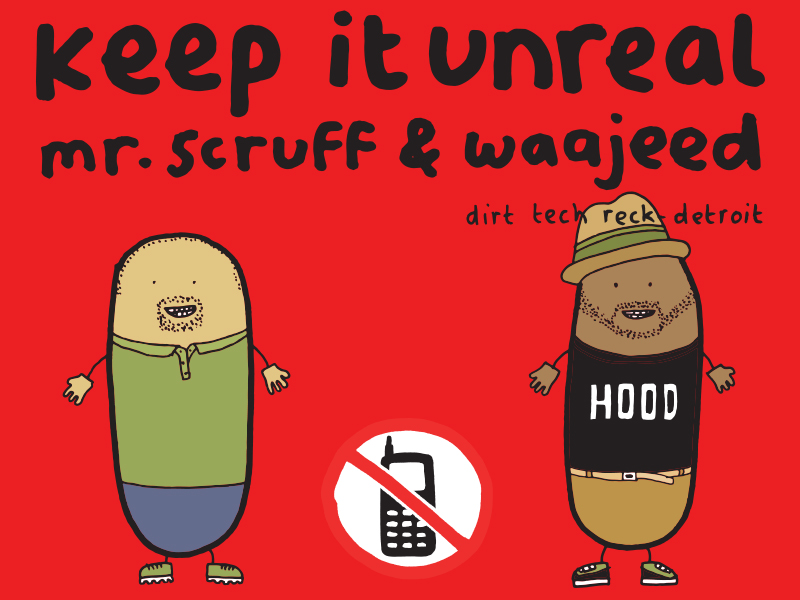

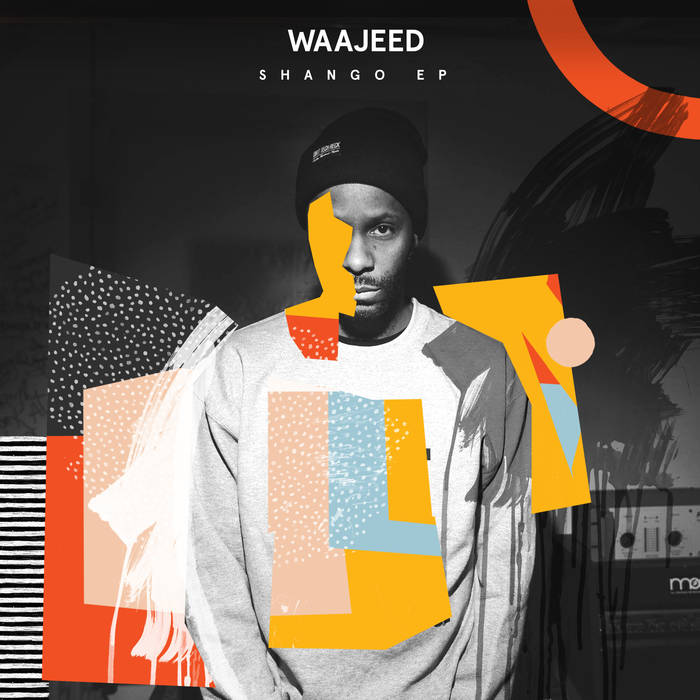

Platinum Pied Pipers came to life in 2002 with Saadiq and an array of friends. In 2012 Waajeed founded DIRT TECH RECK, with an ear for showcasing progressive music ‘from a forgotten city’. It’s on this homegrown label that his latest, dancefloor oriented works appear: his most recent releases are the Through It All EP and before that, Shango.

Waajeed was in Manchester to spin with Mr Scruff at Keep It Unreal over at Band On The Wall, and was gracious enough to lend me half an hour of his time on an empty stomach. Thanks to Waajeed and Scruff!

Read about Waajeed’s five favourite artists over at Bonafide‘s sister article.

An edited version of this interview appears in January 2018’s Now Then Magazine.

So what you up to? You strike me as someone who doesn’t sit still. You remind me of my mother.

Ha ha, that’s good. Oh man, there’s too much to mention, you’re probably right, I’m like your mom, I keep moving. I consider myself a shark. You gotta keep moving, or you die. I’m just finishing the final touches of an EP that I’m putting out on Planet-e with Carl Craig, so that’s gonna be a three or four track EP. I’m just finishing that, as well as new material that’s coming out, the next three releases that’s meant to come out on DIRT TECH RECK, my own imprint, for next year. I’m in the midst of finishing and producing and mixing, and arranging videos, all the content for the next four albums that I’ll put out.

If it wasn’t me I would think that somebody ghost produced it.Do you act as executive producer on those releases?

With the exception of the thing that I’m doing with Carl Craig, yeah I’m the executive producer. I see it from top to bottom, from the very beginning, when it’s dancing the Shango (laughing) to when it’s off to college.

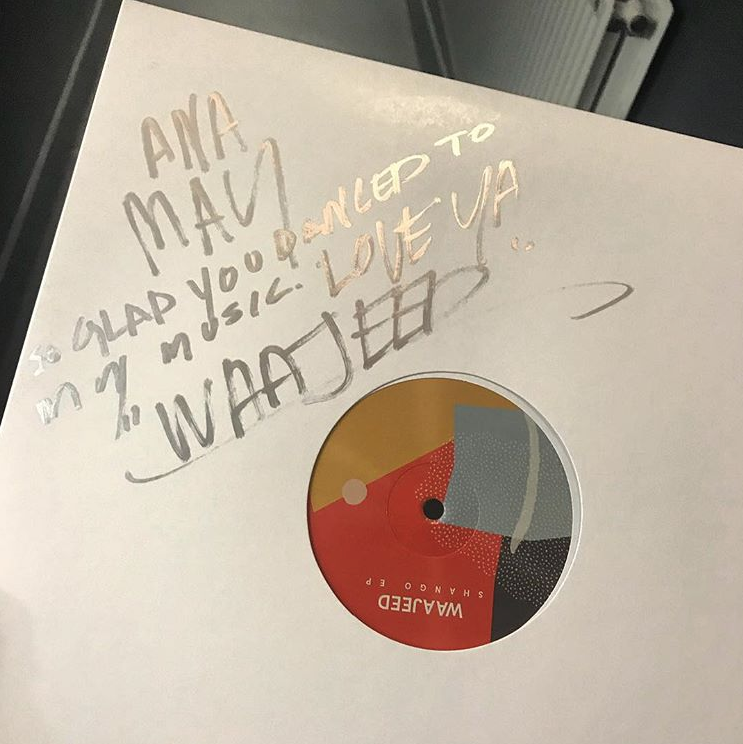

Shouts to Baby Groovement.We were just talking, on the way, about how she has composed her first dance and it’s to Shango. (Waajeed said: That’s better than any review.)

Baby Groovement! This is good, I’m on it.

Shango is very tribal, and in a teaser video you explained Shango is the Yoruba god of thunder. What came first? Were you a fan of Shango, has that riff been in your head… what’s the genesis of that track?

To be honest, I don’t know what happened. By definition, music is magic. It’s something that you conjure and then you have a result that people react from. This magic of music is something that I don’t control, I don’t claim to control it. Most times, I produce so frequently, that I don’t even remember the process of how these things can happen. They just fall in my lap. If it wasn’t me I would think that somebody ghost produced it.

Shango was a demo that I did some time ago, and my team heard it and they said man, this thing is really brilliant.

I work a lot but I work fairly slow. I could be sitting on a track for a year, or six months, or maybe two years. Sometimes three. And then slowly cultivate it into something that it is. Shango was one of those tracks, and it just happened very slow over a certain period of time. I had dreams, and I had these really intense visions of the title, how it should look, what should happen inside of it. I followed those dreams and man, it turns out I was right on point.

It seems like a very visual experience, from the artwork to your video teases, to the video itself… you seem very connected to that track.

I am. Everything I do is just as visual as it is musical. We talked earlier about seeing it from its inception to its finish. I’m a visual artist by nature, I’m just as handy with a paint brush as I am with a drum machine. It’s kinda natural to cultivate the vision as well as what it sounds like, because we do live, in the times that we live in, visual is just as important as what it sounds like. If not more.

We talked about attention span earlier too. You’re releasing EPs, not an album. What’s the plan?

I let the music decide whether it should belong to an EP, or an entire album. Or whether this is just a short burst of ideas, or a longer burst of ideas. I let it tell me what it should be, how it should fit and how these things should work. It just so happens with the Shango EP that those songs fit really perfectly together. In some kind of weird way, where they have no relation but they all come from the same quilt. I don’t pay much attention to what or how people are doing, so much as the music is my teacher. It sets the pace and it sets how things ought to be.

Tron was a big track for me, the time it was released on Fat City (it had previously been out on Bling47). More recently, Thundercat had a track called Tron Song named after his cat, and that always reminds me of your track. And then I found out about Winston! Tell me about Winston, is she your cat?

Maybe in some ways it’s hindered my career, but it has not hindered my soul. It’s been very helpful to do what the fuck I feel. I’m in perfect company tonight with Mr Scruff.My partner just moved in with me, and she has a cat. Her cat’s name is Winston. She’s an older cat, I think she’s about 8. Basically, she’s a granny cat at this point. We have a turbulent relationship to say the least. When things work, it works. When it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

The only thing about Winston is that most of the time I’m up late at night working. As any person with cats will know, you’re in their time, at midnight. Any time after midnight, they’re scurrying around, it’s their house. While I’m developing this track to finish it for the EP, I felt like Winston was scurrying around dancing, for the duration of it. That’s why I decided to give Winston a shout out for this.

I talked to Danny Brown about his Bengal, too.

He’s got two, right?

Bengals are crazy.

It’s a good balance for Danny (laughs), he’s a crazy boy.

There’s a quote from you that I love about not knowing what genres were until your early twenties. Would you say that open mindedness is typical of all Detroit musicians?

I would say, of course I’m a little biased, we may have a leg up in terms of being genreless. We have an imprint in almost all genres. Particularly myself, if I think about it, I was raised up on a radio DJ called Mojo. Mojo played everything. My uncles went to college, so they had a really huge diverse taste in music. I was raised in a house where there were no boundaries. Except for Motown, you couldn’t play much Motown in my house. Me not understanding genres, commercially it can be a hinder, because over the twenty years i’ve been producing music, the key to consistency and building a career is doing the same thing over and over, and you build that market. Maybe in some ways it’s hindered my career, but it has not hindered my soul. It’s been very helpful to do what the fuck I feel. I’m in perfect company tonight with Mr Scruff.

Scruff’s from Stockport, Manchester, a city that has a great industrial history, as does Detroit. They’re both cities that have come out of that now. Both have had thriving musical outputs. How much do you think those two things are related?

When I arrived here, you know I haven’t been here in years, I can’t remember the last time I was here… this place felt deeply familiar when I touched down.

Normally, there’s a bit of anxiety before a gig, a bit of anxiety in a new city. When I got here, I felt none of that. It feels extremely familiar, familiar in a way that’s kinda spooky. I think that I recognise this resilience that comes from the city. I recognise the working class men and women that actually build the countries. There is a striking resemblance between these two sister cities. I’m really happy to be here tonight, and ready to rock.

Nice to step off and feel that when travelling.

It’s rare, it’s rare.

So do you feel anxious playing in a new city?

Sometimes, you know. The job is the job. My job is to come and share good vibrations, so the job is the same everywhere you go, it just really depends on who you’re playing for. Younger, older. For me, it’s the same approach. You just shoot from the hip, you do what feels right in your gut, most of the time it works out.

Most times (laughs).

You’ve gone back to Detroit.

Yeah, I’ve been back for some time, six or seven years.

When you moved back from New York… how long were you there?

I was in New York for eight, almost nine years.

So was it a big creative focus when you got back home? When you moved back, how did that affect you psychologically? I think your environment shapes you massively. Am I wrong in that?

Yes and no. I would say that while I was in Brooklyn, I became more of a Detroiter than I ever had been. My Detroit aesthetic and Detroit point of view applies everywhere I go. I spent quite a bit of time in California as well. I just became more of a resilient Detroiter. I would never wear a New York hat or a Yankees hat, which had nothing to do with baseball whatsoever, just more like, fuck this shit, I’m representing my city.

When I moved back to Detroit, I moved back to the Underground Resistance camp, Mad Mike had a space available… at least he told me there was a space available, inside of the Underground Resistance headquarters. I thought to myself, in my mind I’m rekindling myself with dance music, I’m thinking more about this Detroit spirit, I thought this was the perfect place to move from New York to.

On the day that I was meant to move, Mike said, oh man, your room is not available, something happened. He said, you can move into my studio. So here I am with this bed, in the studio with all this equipment that Mike has made genre changing tracks with. It was just the best thing that could have ever happened to me, because I had access to all that music. At that time I made Scorpio, I actually made a couple of tracks that will come out later this year. It was just a great thing, it was a perfect situation for me to move from New York, and what’s more Detroit than Underground Resistance?

What was the Manchester link back then, with the War LP appearing on Fat City?

That happened with my manager, Max, who introduced us to Fat City at the time. He was going to college here, so I spent quite a bit of time here, back and forth. This was our base of operations. So I would stay here for weeks on end, before the tour, during the tour and after the tour, I would stay here in Manchester and actually make music and work. I think that’s maybe why there’s so much familiarity here. It feels a little bit like home. It feels like the very genesis of this whole journey of music and growth.

Straight to Europe. Which we had no idea where it was. No fuckin’ clue. No clue. It went from… you don’t expect to make it off the block. Unless they fuckin’ carrying you away in a fuckin’ bag.So that was going to be a comp and you remade it?

They asked me to license tracks that were on Bling47. I tend to overkill, so if you ask me for an answer, I’ll give you 12 answers. So I was like, I don’t want to rekindle the same old shit, I would like to do something fresh and do something new. That was a truly, truly chaotic time in my life between travelling, my brother died that year. Crazy relationships, just learning so much as to who I was. Internally, I was kinda like, complicated and rough. It felt like what that album was, rough. That’s why it sounded the way it did. A rough record. I don’t even listen to it anymore, not so much. Even though there’s some brilliant tunes on there. The one I did with Ta’Raach.

(I pull out the twelves, ask him to sign them and he reflects over the track listing.)

Tron, yeah. Wow, Place Where We Dwell, that was great. This one…

I love the skit, spell my name right.

Oh Jesus… It’s still a thing! On email, on everything! On posters.. damn, man. Fuck. Can we just get this right man, in the spirit of making an effort.

Bombs Away, that was my favourite track! Still one of my favourites. It was deeply inspired by Hank Shocklee. All those guys, Public Enemy, it even references samples from those records. Deeply, heavily inspired by how they made music out of chaos.

I remember you playing a lot of this out at Friends and Family, messing with the Funky Worm sample…

Some of these tracks were tracks that we already had. Tron was a track that I’d done years previously, that was Fat City’s inspiration to relicense Bling47 material. They heard Tron, they heard the Jay Dee instrumentals, of which we were the first people to ever put a Jay Dee instrumental out.

And what was the name of that?

Jay Dee Unreleased Instrumentals Vol 1. We did three volumes. I’m happy to say that we played a part in the whole instrumental phase of hip hop as it is. There were a couple of tracks that we already had, Tron being one, and pretty much everything else was new. Tiombe Lockheart, this was her own track, this was one of the only tracks on the album that I didn’t touch, because it just felt so raw and so New York at the time. You listen to that track and she was talking about Williamsburg before it was what we know it to be now. Make Dough, W-A-A-J-E-E-D, all of this stuff, that’s all new.

When you didn’t go to art college and decided to go on tour with Slum Village, were there lessons you learned then that you carry forward now? How old were you?

Early twenties, maybe. It was the first time I had gotten drunk… I was 25. So between 23 and 25. Straight to Europe, no American dates, they hadn’t come together yet. Straight to Europe. Which we had no idea where it was.

(laughing)

No fuckin’ clue. No clue. It went from… you don’t expect to make it off the block. Unless they fuckin’ carrying you away in a fuckin’ bag. So we had no idea where we were going, what it meant… I tend to not think about lessons as musical lessons when I’m learning about the business, the industry, whatever. That information will come and go. I try to learn about things that are life lessons. Friendship, and business, about assets, being smart, so that you don’t have to make bullshit decisions. I learned that in New York, too. Be smart about your business and all of these things that are life lessons, are not applied just to music, so that they impact everywhere that you move. I tend to be the same person off camera and on camera, I tend to do the same things. Too many lessons I’ve learned. Some, at the expense of the lives of my friends. and some at the expense of my own creativity and my own life. Tons of lessons.

I’m happy to say that we played a part in the whole instrumental phase of hip hop as it is.Thank you so much for your time, man.

Thank you man, I know that was a lot!

It was emotional! I knew it would be.

This shit is from the heart, man. I’m so glad to be here, I’m glad you pulled these out, I might play these tonight!

WAAJEED BANDCAMP FACEBOOK TWITTER SOUNDCLOUD

DIRT TECH RECK TWITTER SOUNDCLOUD